Where to Sell Surreal Digital Art Online Cheap With Profits and Printing

"It's actually a lot simpler than you remember." It'south a Tuesday afternoon, and somewhat to my surprise, I'm on the phone to Paris Hilton, who is graciously explaining the world of NFTs.

Hilton is many things – a reality star, an heiress, an unlikely lockdown fettle guru who uses designer handbags instead of weights. But until now, she has never been considered a significant player in the fine art world. When artists have acknowledged her, ofttimes they've done so to fetishise her epitome. In 2008, Damien Hirst bought a portrait of her by the artist Jonathan Yeo, in which her body is constructed from collaged images cut from porn magazines.

Yet in the by yr she'southward become a surreal figurehead in the NFT scene: a globe flush with crypto dollars and high on a promise to transform the worlds of fine art and commerce. When we speak, Hilton has just returned from a bitcoin conference in Miami, where customers paid up to $25,000 for VIP tables at the opening party to watch her DJ in a pair of diamanté-encrusted headphones. "NFT stands for non-fungible token, a digital token that is redeemable for a digital slice of fine art," she explains. "Yous tin have it on your figurer server or your phone. I take these screens in my house where I display them."

Sure plenty, at Hilton'south Beverly Hills mansion there are screens displaying NFTs she made in collaboration with the digital artist Blake Kathryn. These include a video of a chihuahua on summit of a rotating ionic column (a tribute to her deceased pet Tinkerbell) and an animated self-portrait of Hilton as a sparkling CGI Barbie floating in the clouds, a piece she'due south called Iconic Crypto Queen, and which she sold in April for more than than $1m.

Hilton first started investing in cryptocurrency in 2016. "I became friends with the founders of Ethereum," she says. (Ethereum produces ether, the currency in which the majority of NFTs are traded.) Since so she's thrown herself into collecting crypto art, and owns more than 150 NFTs.

To advocates of the NFT, the technology offers a revolutionary new mode of selling fine art, and of circumventing snooty cultural gatekeepers whose resistance to a crypto time to come seems equally square equally the 19th-century Parisian art world'south disdain for impressionism. In this context, the relevance of Hilton's make to the NFT movement makes sense. Pinkish, jewel-encrusted, and openly motivated by being as rich and famous as humanly possible, she's a far cry from the type of person whose work is typically exhibited in baddest galleries or hung in booths at fine art fairs.

Yet Hilton's endorsement may as well be ammunition for those who view the NFT every bit but another depressing example of the speculative logic of finance monopolising taste. To detractors, from critic Waldemar Januszczak to artist David Hockney, the NFT marketplace is a domicile for morally broke, environmentally vandalistic money-grabbers whose creations barely qualify as art.

While most of the states are still trying to recollect what "fungible" means, a boxing is nether manner to ascertain how NFTs are understood. Are they a vital cultural product that tells us something profound almost digital consumerism? Or are they just the latest cynical way to make absurd amounts of coin?

A motley crew of celebrities have tried their manus at selling digital art, including Snoop Dogg, Lindsay Lohan and John Cleese. In July, it was estimated that sales of NFTs in the commencement one-half of 2021 rose by more than $2bn (£i.47bn) – a trend that prompted Christie's and Sotheby's to host their own NFT auctions and that is credited with driving contemporary fine art sales to an all-fourth dimension high. But only a tiny proportion of the gain of art NFTs have ended up in the bank accounts of the galleries that have, in addition to auction houses, traditionally taken the lion's share of art-marketplace profits.

In March, the crypto firm Injective Protocol paid $95,000 for Morons, a physical artwork by Banksy depicting an auctioneer selling a framed motion picture bearing the words: "I can't believe you morons actually buy this shit." They and then burned the motion picture earlier selling a digital token of the work for $380,000. The event was a marketing ploy, designed to stoke outrage, drum up publicity and turn a profit. Yet the symbolism was stiff: digital fine art is here to supersede its concrete forebear, and its coming supremacy should be reflected by a college price tag.

In essence, an NFT is a digital certificate of ownership, virtually always bought and sold using cryptocurrency, to which any digital file – a jpeg epitome file, a video, a song – can be attached. That Hilton is able to display Iconic Crypto Queen in her abode, despite having sold it, is part of the NFT's appeal – and the claiming information technology poses to the established business model for trading and accessing art. With a elementary Google search, anybody can find and download the file associated with an NFT for zilch, and store it on their telephone or computer, simply only the owner has the right to sell information technology. Each NFT is unique, and all transactions are logged on the blockchain, a type of database invented in 2008 for the purpose of recording the movement of cryptocurrency.

Unlike the commercial gallery business model, NFTs are designed to cut out the need for art dealers, enabling artists to trade directly online, typically via specialist auction sites. Crucially, in contrast to the gimmicky art world, there is no "vetting" of collectors – a exercise intended to stop the most speculative buyers flipping artworks by speedily reselling them at a profit. Everyone can buy an NFT, and prices, then frequently a thing of mystery in high-end commercial galleries, are listed every bit a matter of public record. Every time an NFT is resold, its creator also makes a profit – an inbuilt royalty system missing from the physical fine art world, where artists often feel as if they have been shafted when their piece of work is resold on the secondary market place.

A model for trading and sharing art, built on the principles of financial transparency, royalties and easy access for all may sound egalitarian. The reality has been rather dissimilar. As soon equally it became apparent that almost anything digital could be labelled equally art and sold, the circus rolled into town.

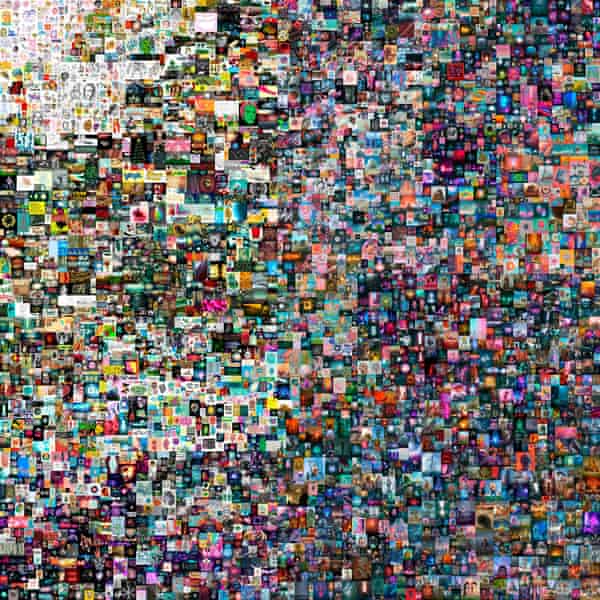

In March, Everydays: The First 5000 Days, a collage of previous artworks by a 40-year-erstwhile American named Mike Winkelmann, amend known as Beeple, sold for $69.3m at Christie'due south New York. After that, Kate Moss sold a gif of herself for more than than $17,000. Jack Dorsey, CEO of Twitter, sold an paradigm of the kickoff ever tweet for $2.9m. A Brooklyn picture managing director managed to sell an audio file of his own farts for $85. Dominic Cummings fifty-fifty threatened to utilize the engineering science against Boris Johnson, by releasing what he said was evidence of government malpractice in the class of an NFT.

Along the way, the market became gratuitously inflated. Bidders at the top cease included Vignesh Sundaresan, a blockchain entrepreneur who bought Beeple's $69m NFT. A considerable number of small-time enthusiasts were too ownership at the affordable end of the market, dandy to celebrate the engineering by investing in blockchain art. It didn't take long before the bubble burst. By May, daily sales of NFTs had dropped by 60%. Crypto art's reputation has also taken a knock because of its awful ecology track record. (The annual free energy consumption of Ethereum is estimated to equal that of Iceland.)

Despite this, advocates still believe NFTs can mount a challenge to the monopoly on trading art held by commercial galleries, and even create a future where physical artworks are replaced past their digital counterparts. As Hilton puts it: "In that location are paintings out there that are $100m or more, simply if y'all call back about it, it's really just canvas with paint."

I n the beginning, before the circus pitched up, there were nerds. Inevitably, because this is the internet, in that location were also cats. CryptoKitties, to be precise, is an online game launched in 2017, enabling players to trade and "breed" unique cartoon felines, sold as NFTs, using blockchain engineering. Although the first NFT was created by a man named Kevin McCoy in 2014, CryptoKitties attracted attention and money, with some cats trading for hundreds of thousands of dollars. During 2020, every bit cryptocurrencies boomed and the pandemic accelerated our transformation into a species of screen-obsessed zombies, interest in NFTs rapidly picked upward stride. Equally a consequence, the value of work by a relatively pocket-sized number of artists already on the scene rocketed.

Among them was Trevor Jones, a 51-year-quondam painter who lives in Edinburgh. You've probably never heard of Jones, but he's the virtually successful NFT artist working in the Britain. He started making NFTs in 2019. "Five years ago, I was struggling to pay the mortgage," he tells me. "I went from having to borrow money from friends to pay the bills to making $4m in a day."

Jones has made a proper name for himself combining painting with digital engineering science, often producing pastiches of famous artworks with a crypto twist. In 2020, Bitcoin Bull – an blithe painting of a Picasso-inspired bull, decorated with bitcoin logos and Twitter birds – was bought by a prominent crypto collector named Pablo Rodriguez-Fraile for $55,555.55.

Jones is warm, unguarded, and stunned by his rapid rise. "I grew upwards in a piffling logging community," he says of his babyhood in western Canada, a place he describes as "rough". "When I was 25, a friend of mine ended upward getting into a fight at a bar and was killed." He left before long after, eventually settling in Edinburgh, where he worked at the city's Hard Rock Cafe as a waiter and afterward equally a managing director.

Jones tells me about the mental health crisis he suffered in his early on 30s. "My girlfriend and I broke up and it kind of all came crashing down. At that point, it sounds cliched, but I decided I needed to find something to save me."

He set his centre on condign an artist and "begged" his style on to an art foundation grade at Leith School of Art, which he followed with a degree at the University of Edinburgh.

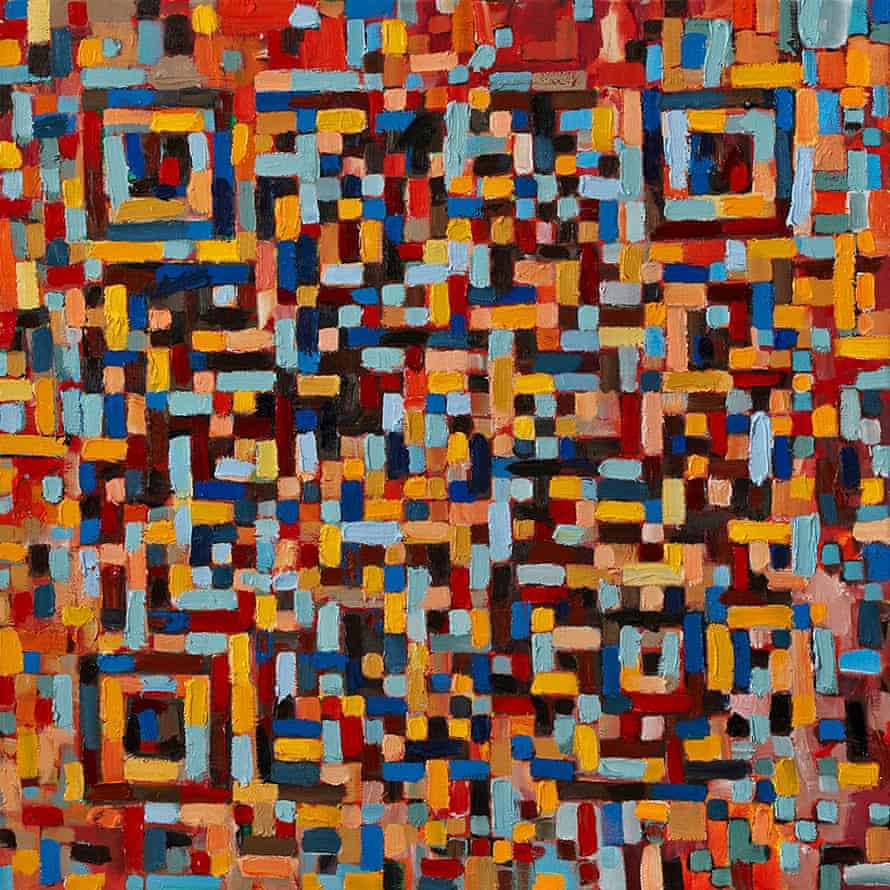

Things began to look upward for Jones in 2012, when he had the idea of incorporating QR codes into his art, painting the scannable barcodes in Mondrian-like colours on canvas. Scanning the paintings takes viewers through to an online gallery, where anybody tin can upload their piece of work. "People were laughing at me at the time," he says. While gallery audiences turned their noses upwards, he gained a new following online, one that would plough out to have deep pockets.

In 2019, Jones began working with animators to turn his paintings into short videos that he sold as NFTs. Amongst his well-nigh successful works is Bitcoin Angel, an NFT based on Bernini's bizarre masterpiece The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, which he sold in 2020 for the equivalent of more $3m (all of Jones's NFTs are bought using cryptocurrency). In Bernini's marble sculpture, a nun has been stabbed in the heart by an affections with a spear. She leans backwards, overcome past the sublime ecstasy of existence penetrated by a heavenly body. When the arrow pierces the heart of Jones's nun, she bleeds bitcoin.

To sell Bitcoin Angel, Jones used a website called Dandy Gateway, 1 of a number of online auction sites designed for trading NFTs that are now flooded with aspiring crypto artists. I dedicated an afternoon to scrolling through the lots, each 1 flashing and jiggling in the hope of attracting the attention of collectors. I saw gifs of muffins transforming into dogs, spinning trainers, sycophantic portraits of Elon Musk and an affluence of naked, big-boobed cyborgs. The art critic Dean Kissick described the male-dominated NFT scene every bit "Etsy for guys", and on this evidence it's piece of cake to see why. Aside from the headline-grabbing sales, Bang-up Gateway provides a platform for aspirational entrepreneurs and hobbyists, who practise their craft on computers rather than knotting macrame plant hangers.

While those – like Jones – who successfully rode the NFT moving ridge were busy counting their crypto dollars, over the past twelvemonth the conventional fine art world has suffered a turn down. During the pandemic, with audiences unable to physically nourish exhibitions and fairs, art dealers have struggled to brand online viewing rooms interesting or lucrative. Equally a outcome, global sales of art fell by 22%. To rub common salt in that wound, millions of crypto dollars were exchanging hands for a natively digital art form. "The technology is designed against the existing art globe," says Noah Davis, a specialist at Christie'due south New York. "It's an art form that doesn't need a gallery."

It was Davis who helped to sell Beeple's $69m NFT, the first slice of crypto art ever listed by a major auction house. He views his own touch as pivotal: "I introduced NFTs to the Christie's audition and thereby the world," he says. The artwork was sold during an online sale in March that took two weeks to close. Bidding opened at $100, and inside an hour that effigy had risen to $1m – the result of a vast number of bids all happening digitally. "I've never seen anything and so spectacular. You tin't bid that quickly at auction unless yous merely shout out: 'A one thousand thousand bucks,'" Davis says, "and that'southward incommunicable to practise online. So all that behest had to happen in increments and manually.

"I look at my life as pre-Beeple and mail-Beeple," he adds. "The aforementioned manner the world thinks nearly before Jesus Christ and after. Beeple is kind of my Jesus."

In the months since, Christie's has connected to cash in on NFTs. In May, information technology achieved $xvi.9m for nine pixellated cartoon characters from the CryptoPunks serial, early examples of NFT art that take get sought-after collectibles. Christie's has also attempted to unite the crypto and mod art markets. This bound, it hosted a sale of digital artworks made by Andy Warhol in the 1980s. The images, which had been recovered from floppy disks and transformed into NFTs, include drawings, made on the artist'south Commodore Amiga computer, of bananas, flowers, and of a Campbell's soup can that alone sold for more than than $1m.

In general, the commercial gallery globe has been understandably chary most adopting applied science designed to circumvent information technology. Behind the scenes, all the same, a number of galleries have attempted to woo Jones. He has declined their advances. "What tin can a commercial gallery do for me?" he asks. "Having a gallery exhibition before, I worked a year creating paintings, I paid for all the framing, the overheads for the studio. I had the paintings delivered to the commercial gallery. I may or may not sell, the gallery takes 45 to 55% committee, and they might pay out a calendar month, half-dozen weeks, two months later." And now? "I sell something and iii minutes afterward I've got the money in my digital wallet."

A t times, the divide between the two art worlds seems more than profound than a difference in business model: it's an all-out culture clash. "Few of these cyber-millionaires could tell the back of a Rembrandt from the front," wrote art critic Waldemar Januszczak. "In that location is no claiming whatsoever in NFT fine art," conceptual art collector Pedro Barbosa told the New York Times, arguing that the ideas behind NFTs are often derivative, having "already been explored by artists like Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Duchamp". David Hockney branded NFTs "lightheaded little things" for "crooks and swindlers" – a curious accusation from an artist happy to embrace and monetise novel digital technology. Since 2009, Hockney has been doing a roaring trade in souped-up iPhone and iPad drawings.

Jones tells me that the crypto true-blue, who, like Hilton, ardently believe that NFTs are the hereafter of fine art, now apply the dusty epithet "the legacy art world" to refer to their physical rivals.

As a painter, Jones is unusual amidst NFT artists. On occasion, this has allowed him the opportunity to sell the original painting on which an NFT is based, every bit well as the NFT. Pulling off this kind of double sale, still, must exist handled carefully. Charging more for a painting than an NFT, and thus valuing concrete art more highly than digital art, could provoke the ire of the crypto crowd. When Jones sold Bitcoin Bull to Rodriguez-Fraile, he also sold the original painting to the second-place bidder. In order not to offend his fans, he priced the painting at $55,000 – $555.55 less than the NFT.

A handful of established contemporary artists, notably those who have form when information technology comes to explicitly courtship headlines and extreme wealth, take tried their hand at making NFTs – most prominently Damien Hirst, who released the projection The Currency in July. Hirst put 10,000 NFTs upwardly for sale, each corresponding to a unique spot painting, for $2,000 a piece. But there is a take hold of: after two months, the collector must decide if they wish to go on the NFT or the physical art piece of work. Whichever one they don't cull will be destroyed, forcing the owner to gamble on which version volition exist more than valuable in the future.

The most shocking attribute of the NFT to the fine art intelligentsia is its brazen entanglement with finance. Trading art has e'er been a pastime of the wealthy. Much of what counts for fine art history consists of flattering portrayals of the rich and powerful, and artists take long been expected to perform what Tom Wolfe called the Fine art Mating Ritual – attracting the interest of wealthy patrons and bourgeois institutions, while simultaneously presenting as Bohemians and renegades. Yet with the NFT, the stardom betwixt art and nugget seems to have disappeared. In place of the curated exhibition is the auction website; symbols of the market have seeped into the aesthetic language of the art itself. Prices, non ideas, dominate.

Despite the promise of "art for everyone", the final destination of the NFT might not actually be art. Art may merely be a useful mode to advertise the possibilities of a new technology. "I've done everything from style, fragrances to endorsements," Paris Hilton says, adding that NFTs are another way for "fans to have a piece of me". As well as working with the rapper Ice Cube, Jones recently made an NFT for the whisky company Macallan, to be auctioned alongside a very expensive cask of scotch. This, it seems, is a taste of where NFTs may exist heading: not a radical new model for trading art, but a digital marketing bauble.

Peradventure the most pregnant legacy of the NFT'south assault on the art market volition be the questions it forces us to ask about the nature of art, and what it is that nosotros want from information technology. How should art be traded and viewed? Who gets to ascribe value to art? Is there a moral or aesthetic lawmaking by which artists are expected to work, and who has elected themselves to define it? And why would anybody part with their coin in exchange for a digital fart? So there's the biggest question: is there a meaningful divergence betwixt an artwork and an asset? The reply, perhaps, is not always – but if we want art to exist more than than a tool for prettifying finance and flogging merch, then it'southward an ideal worth holding on to.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/nov/06/how-nfts-non-fungible-tokens-are-shaking-up-the-art-world

0 Response to "Where to Sell Surreal Digital Art Online Cheap With Profits and Printing"

Post a Comment